|

There is now doubt that this past year has created a tidal wave of change in education.

Alyson Klein's February 18 EdWeek article "The Pandemic is Shaking Up the World" is the latest in a rash of articles and blog posts and Twitter conversations that proclaim the changes that the pandemic has wrought. We all wonder--often excitedly--about how our experiences of the past year will shift how we "do education" as a country. But what about the shadow-side of that same question: What happens when COVID is no longer a driving force for change in education? I have to be honest; as an administrator whose role focuses heavily on designing and delivering professional development, I have reveled in the enormous surge in motivation for professional learning over the past year. I have watched with relief as some of the 21st century strategies and practices that were so hard to establish pre-COVID have become daily routine simply because they had to. Edtech tools are being used more consistently and creatively than ever before. Curriculum and lessons and assessments are being redesigned, often for the better. Faculty who were extremely resistant to change have become more open to new ideas and practices. The optimist in me believes that this marks a moment of educational revival; that we will truly re-think and re-design many of our practices and systems that have previously been untouchable. But I worry that this could so easily be a temporary phenomenon. We are only human, and such fast-paced growth is exhausting. Educators have lived in survival mode for nearly 12 months; we've had scant time for the reflection needed to make openness to growth a more permanent habit. And as soon as the external pressures created by a pandemic reduce or disappear, it would be so easy for educators around the country to breathe a sigh of relief, disengage, and fall back into the old familiar, comfortable patterns they have relied on for years. I can't bear to see that happen--not when we've come so far. So educators, let's make ourselves a promise. Let's make time before the end of this year to reflect with purpose. Let's review, evaluate, imagine, and commit to continuing the design work that we were thrown into this year. Let's remind ourselves of what our students will likely experience in their college and professional lives, and make sure we prepare them for it. COVID might have triggered change, but let's put ourselves back behind the wheel and make this journey worth it.

0 Comments

Most educators are unsuspecting designers. Over the past year, I've determined that this truth is a powerful one. Educators at all levels design every day--lessons, activities, interactions with students and colleagues, faculty meetings, programs, events, policies, communications...and on and on. Yet, unless they have recently attended conferences or workshops in which design thinking is highlighted, many educators engage in this design process on a purely instinctive level. Does that work? Sure it can. But I've become convinced that making the design process visible through design frameworks from organizations like Stanford d.School can help educators be more successful in their process. More importantly--perhaps most importantly--educators who commit to developing a design-thinking mindset can experience growth in self-confidence, better connections with their students and colleagues, and reduced stress in the face of the inevitable challenges that they face in the course of each day. So what do I mean by a design-thinking mindset? Educators who embrace this mode of thinking:

An educator's ability to calmly navigate through increasingly speedy change will become, in my opinion, an essential skill. What better way to develop that ability than to study and visibly integrate design thinking frameworks into our everyday work. For some ideas on what this can look like and where to start, check out my recent webinar through ISTE's ETCoaches Network (see below). And if you are in Seattle for NCCE 2019 next week, come to my session where we will dive deeper into these ideas! Exactly one month ago I took a new leap--in this case, from being an instructional coach at one school to being a vice principal at another. Can that be true? It is as if the past month proceeded at light speed; in a mere few days it will be time to welcome a new school year. I have often thought that the first day of a new academic year is more powerful than New Year's Day for educators. It is the beginning of a new cycle of classes, meetings, lessons, and interactions that are the substance of our professional lives. And of course, my new role makes this time even more poignantly about new beginnings. During the first days of my new job, I listened to The Confidence Code by Katty Kay and Claire Shipman while commuting to and from work. The book had been recommended by a close friend; she thought it would be of benefit to me during those initial nervous days. She was right, I dare say even more than she realized. "If you choose not to act, you have little chance of success. What's more, when you choose to act, you're able to succeed more frequently than you think. How often in life do we avoid doing something because we think we'll fail? Is failure really worse than doing nothing? And how often might we actually have triumphed if we had just decided to give it a try?" The Confidence Code, Kay & Shipman These words could not have been more timely. Because of these words, I mustered the courage to share my opinions during meetings, to put my ideas for new programs into effect, and to engage in conversations with my new colleagues even when I felt awkward in doing so. When hesitation hovered, I sought new resolution to "give it a try." When the inevitable mistakes occurred, I reminded myself that we learn best from failure rather than success. I am first and foremost an educator, after all. If I don't live this truth, how can I expect my students or fellow educators to do so? Holding fast to this belief will become even more important as faculty and staff return to school to begin a new academic year. Few other professions require the levels of energy, dedication, and generosity that education does. Research clearly establishes educators make thousands of decisions in a single day--more even than a neurosurgeon. (See synopsis of research in "Educator as Professional Decision-Maker" by Concordia University.) This is hard, sometimes thankless work, and it can be easy to slip into the status-quo just to make life a little easier--to stick to the same curriculum, keep the same assignments, offer the same lectures, grade the same way, or refuse to incorporate new strategies or tools because of the energy that will require from an already-stretched brain. And yet...and yet...this is what we simply cannot do. The work and content may be familiar to us, but for the students who walk into our classrooms this fall, it is all brand new. They are not the same students who walked in last year, or five and ten years ago. And now more than ever, they need to see us do what we ask of them: "give it a try." I think Neil Gaiman's 2011 "My New Year Wish" puts this best; allow me to gratefully borrow his words as my wish for all of us in this new school year. “I hope that in this year to come, you make mistakes. I have never considered myself to be artistic. In fact, I've won contests for "worst teacher whiteboard artist" at school--yes, indeed, I could not draw an octopus better than my colleague!

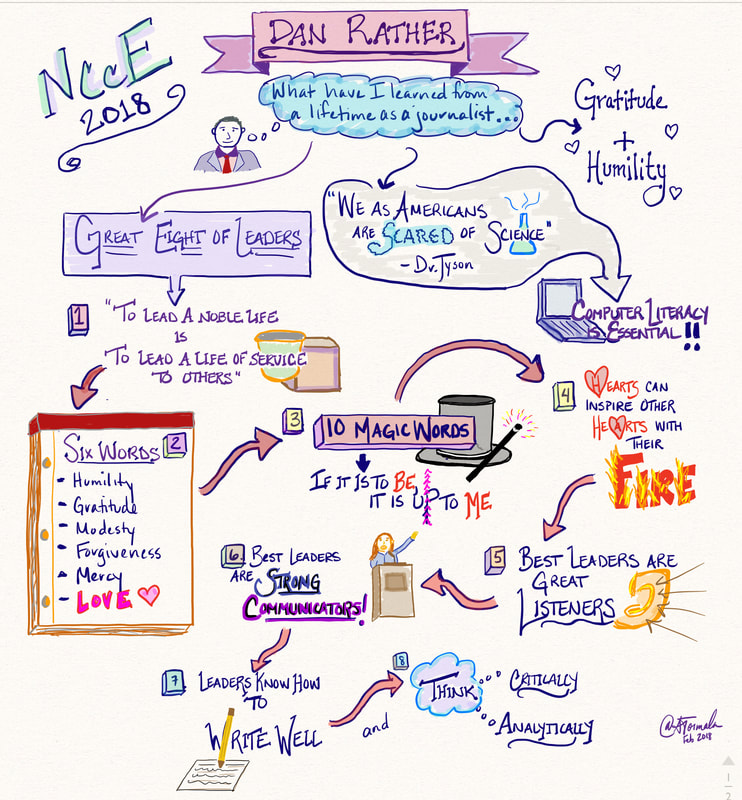

But I have been fascinated for some time with the idea of sketchnoting, not only for my own purposes, but as a learning strategy that currently remains untapped in my school. So when NCCE 2018 featured renowned sketchnoter and Apple Distinguished Educator Sylvia Duckworth, I absolutely could not pass up the chance to learn from this innovative expert in the field. And learn I did! Through participating in partner drawing challenges, mystery icon activities, and banner and font practice, I realized that Sylvia was right--you don't have to be an artist to be a sketch noter. So I set myself a challenge: sketchnote the NCCE2018 closing keynote by Dan Rather. I paid close attention to the experience and compared it to my usual methods of taking notes. Was I holding on to the information more deeply, as the research suggests? Did I engage with the presentation and connect to the speaker? What might be the downsides of this method? As you can see from my final product, it turns out that Sylvia was right--sketchnoting isn't just for artists. I managed to capture the main ideas from Mr. Rather's speech and present them in a visual, sharable way--and had fun doing it! And I do remember what he said in far more detail than I would have with my regular notes. I noticed that I looked more at my screen than I did at him...but given that I couldn't quite see his expressions from where I sat, I'm not sure that's a problem in this context. So what's next? I cannot WAIT to introduce/emphasize this method to the teachers and students in my building. We are a school full of creative, expressive young women who are always looking for the next best way for artistry and technology to blend. I suspect that sharing a few of the amazing Sylvia's tips and tricks are all it will take to start a sketchnoting revolution!  Last week, I attended the first meeting of a Supervision and Evaluation course I'm taking as part of an administration credentials program. The bulk of our class period was spent discussing the question: Can administrators--who must evaluate teachers as part of their roles--also be instructional coaches? What a hard question to answer. As an instructional coach, my role is deliberately non-evaluative. In fact, a primary argument in favor of having instructional coaches in a building is the idea that teachers are more willing to be vulnerable with a coach than they might be with an administrator, since anything a coach observes or assists with will not have any relationship to evaluation or employment. I have seen first-hand that this model works, as long as the coach is adept at building relationships and approaching other teachers with empathy, patience, and positive encouragement. Yet, can we bring some of that same philosophy into administration? Can an administrator serve both as a coach and as an evaluator? I guess it depends on how well that administrator has build up trust and credibility with their faculty. Dr. David Franklin of The Principal's Desk recently discussed "5 Ways Principals Can Build Trust" in an article on the ASCD Edge. He argues that a principal should:

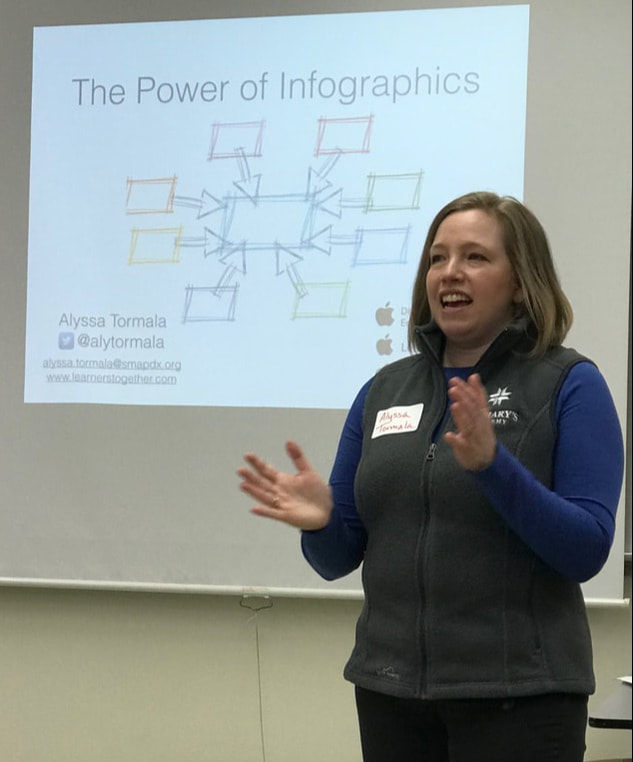

This advice hit home for me. The best supervisors I've had--both in education and outside of it-- have always followed these principles. Their doors were always open and they were always willing to give me their full attention when I needed it. They were direct and open with me about what I needed to know, even when I didn't like it. They took the time to understand my perspective. They stayed current with the work being done by their employees and participated in community events. And they always kept the mission or goal of the work in the forefront--something that we could all agree on, even when we disagreed about the methods by which we met that mission or goal. And as a result, I did go to these supervisors for coaching and mentoring, knowing that they valued what I was learning as much as they valued my results. So...can an administrator be a coach? I think the answer is a qualified "yes". But I suspect that it takes empathy, deep wells of patience, a solid understanding of human nature, and a never-ending trust in people to do their best when given the chance. I hope that I can live up to those standards as I transition into school leadership. Two years ago, I introduced an assignment in my 9th grade technology class called the "Keynote 6-Word Story." Honestly, the idea was born of desperation--I was going to be absent for a day but needed my students to maintain their momentum in our unit about presentation tools. Inspired by a six-word video assignment created by Dan Goble, I decided to challenge my students to create six-word stories using Keynote instead. I was floored by the resulting projects and by my students' enthusiasm. So I couldn't wait to try it again this year, particularly with Keynote's new shapes and animations. Combine those new features with Magic Move...and the results from students are truly magical this time around! Even better, this assignment has opened new levels of creativity for my students with regard to their presentation skills--gone are the tired slides with dozens of bullet points. Check out these two samples for a taste of the possibilities! Want to turn the Keynote presentations into videos? Export them as a Quicktime video from a Mac, or use the new screen recording feature in iOS 11 to record the Keynote on an iPad or iPhone.

I also wanted to try my hand at something that would allow me to create material myself. Then it occurred to me that I could do that AND solve a problem I'd been struggling with all summer.

I serve a hybrid role in my school building--although I am the Instructional Technology Coach, I also usually teach a class or two. But due to scheduling and FTE challenges for my school this fall, my teaching load has increased to nearly full time during the first semester. I love working with students and innovating in the classroom, but I have been struggling with how to balance that work with continuing to support my colleagues, particularly with the quick "in-the-moment" tips and tricks that are the usual bread and butter of my days. Enter Clip That! Clips--a series of quick videos I am creating that focus on small tips to help educators enhance their productivity and creativity. Each video is designed for the busy educators I work with; they are 60 seconds or less and focus on the information, tools, or needs that are directly relevant to my colleagues' work that week. I email them out on Friday afternoons so teachers have a chance to watch and think about the information over the weekend. Simply put, my colleagues should be able to "watch a minute, then save a minute" by following the tip in the video. So far, the videos have ranged from simple tips like creating contact lists in Outlook to more extensive challenges like syncing grades from Schoology to PowerSchool. I've also gotten some creative elements in, like introducing the new Clips app. Check out the videos on the ClipThat! Clips YouTube channel. Is it working? We'll see. Stay tuned for more reflection on this question once my survey data comes in!

In the meantime, check out the videos below that help explain the idea, and please spread the word to your schools and on social media! Don't forget to use #OneStoryForward so we can cheer you on!

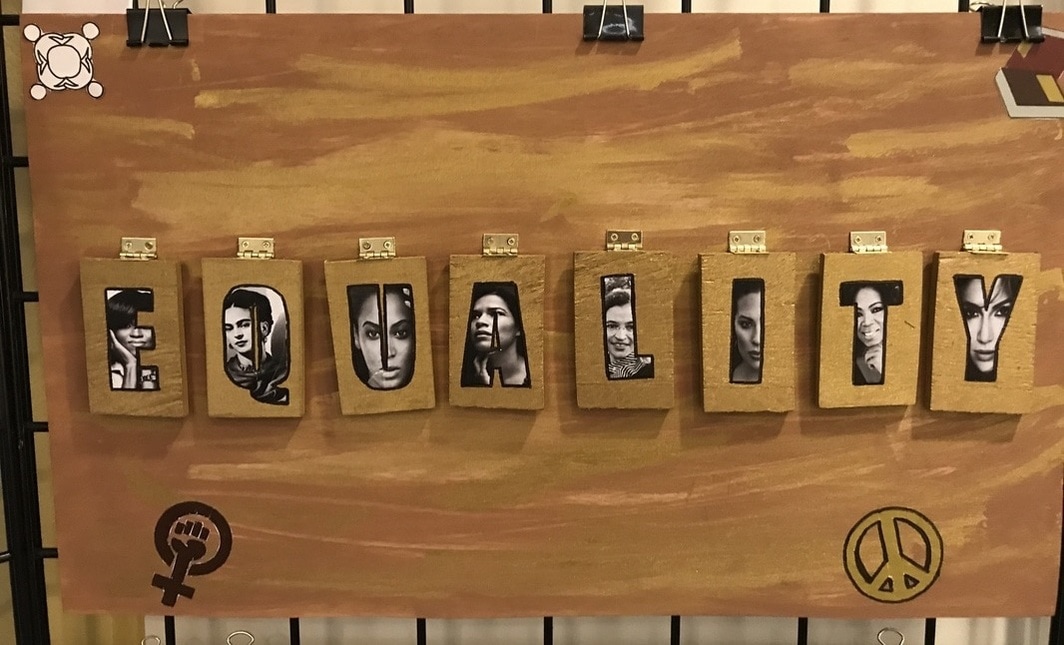

Students' "We Believe" designs were displayed during the last week of school in front of our library. Many of the designs included QR codes sending viewers to videos and other links. Students' "We Believe" designs were displayed during the last week of school in front of our library. Many of the designs included QR codes sending viewers to videos and other links. We did it! I'm still sweating a bit...but I'm still standing. During the last two weeks of the semester, our Speech and Graphic Design students jointly wrestled with interpersonal conflicts, design snafus, confusion over expectations, and deadlines as they worked through their prototyping and testing phases of a joint design challenge. (See my previous post for details about the challenge.) They experienced triumph when design ideas came together, frustration over incomplete work by absent teammates, and satisfaction over final products being displayed. And on the final exam day, they presented what they learned to the full joint class. So what did they learn? I decided to dig a bit deeper with a post-project survey. The results were both satisfying and thought-provoking.

Although many students offered positive feedback and comments about their experiences, a few threads in the feedback will need to be addressed the next time we try a project like this.

But one thread of feedback worries me. Quite a few students expressed frustration over not being given specific expectations for the project--in other words, some of them wanted us to tell them exactly what to do right from the beginning. The inherently messy, uncertain nature of a design process clearly made them feel uncomfortable, and they saw that as negative. This reflects the reduction in resilience and grit that education and youth experts have recently raised as a growing concern (click HERE for a Pinterest board of materials on this subject), and it's one that I have become similarly worried about with regard to my own students. While being able to follow exact parameters and specifications might be easier, it does not prepare them for the astoundingly messy-yet-brilliant experience that is professional life in most fields. Knowing that, I can't help but think we are not serving our students by making their academic experience too predictable. I want students to see a project like this as an opportunity to be creative, outside-the-box solution-finders. But I worry that our society's current systems and parenting styles have made it increasingly difficult for our students to do this. I'm particularly struck by the research of Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan and many others regarding "self-determination theory"--that people are best motivated when they can see themselves gaining competence, acting from autonomy, and finding personal connection to their work. Daniel Pink similarly argues that people are motivated by "mastery, autonomy, and purpose." And the reality is that most of our current "status quo" educational methodologies are not designed to engage the intrinsic motivations of our students. So we fall back on extrinsic motivators like grades. And even those are waning as our students discover and connect with other activities--sometimes benign and sometimes not-- outside school and home. Will I do this again? I hope so. This is my third experience facilitating a design challenge in class, and every time I have worked to reimagine and refine the experience. I never seem to find the perfect recipe, and yet I have come to recognize that teaching is a prime example of the design process at work--so perhaps there is no perfect recipe to find. More importantly, I have learned to thrive on the discomfort that comes from uncertainty. And I believe that my students and colleagues will benefit as a result.

But this time around, I am working in tandem with our Graphic Design teacher whose class meets at the same time as my Speech class. We have created a joint challenge that requires our students to work in small teams of both Speech and Graphic Design students.

Project Background: The theme: "We Believe" (which is the new branding phrase for our school). The objective: Create a large display that reflects what a variety of groups within our community believe. Each team is responsible for choosing a target group and, through the Stanford d.School design thinking process, creating a poster-size design that communicates the beliefs of the target group. The designs will all be added together to create a larger display. This students must then formally present their designs to an authentic audience. The graphic design students are primarily responsible for the visual designs, which can be flat or multi-dimensional. The speech students are primarily responsible for how the information is communicated (either through words on the poster or through an audio/video element that is attached as a QR code) and then designing and running the final presentation. Week 1 Progress and Reflection: May 12 (45 min): We launched our project by bringing both classes together for a quick introduction to design thinking, using David Kelley's TED Talk "How to Build Your Creative Confidence" (see above) as the focus. The lively discussion allowed us to help students think more expansively about what it means to be creative, and to introduce the terminology associated with the Stanford d.School design thinking process. Reflection: I highly recommend David Kelley's TED Talk for this purpose. It's 11 minutes long, leaving plenty of time for engaging discussion. I asked students to come up with the questions a designer would have to ask to fix a product, and that led us very smoothly into the terminology. I was really pleased with this experience. May 16 (85 min): Students were introduced to their new joint teams, then led through a 70-minute "Crash Course" design challenge, loosely based around the Stanford d.School Crash Course. Students engaged in the Empathy, Definition, Ideation, Prototyping, and Testing phases to create an item their partner could use for their lockers. Not only did this help solidify the concepts of design thinking, but it allowed the new teams to get to know each other a bit better. By the end of the class, the teams had also chosen a target audience for their actual design challenge. Their homework was to interview at least 3 members of the target audience. Reflection: A crash course is always an exercise in structured chaos, and students who are used to more "traditional" methods of learning often scoff a bit at this experience. But by the end of it, they are having fun and usually asking for more time to prototype. I was happier with my revisions to the instructions this time around--having them design something for a locker worked well--but I found that trying to run this with 50 students was a lot more challenging and left us less time for reflective discussion. Next time, I would split the teams into two classrooms and have each teacher run a challenge. May 18 (85 min): This was Day 1 of our actual design challenge. Today we focused on definition and ideation. Class started with the Stanford d.School post-it note activity, found in The Bootcamp Bootleg (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0). From there, students filled out a modified definition statement, then jumped into ideating potential designs and plans. Reflection: Students expressed confusion and discomfort at not having exact instructions on what to do. We had deliberately chosen not to give them too many parameters, fearing that it would limit their creativity. But I did worry that perhaps the confusion was also getting in the way. After the class, the Graphic Design teacher and I decided to spend a little time separately with our classes the next day to clarify our expectations. May 19 (45 min): We spent 30 minutes in separate classrooms, going over our joint rubric and the specific expectations for students in each of the two classes. We then got the teams together again for 15 minutes for quick team meetings before heading into the weekend. Reflection: This was a much needed and appreciated "time-out". Going over the rubrics helped us clarify the general expectations and alleviate confusion over process and final product. My Speech students were more relaxed by the end of the 30 minutes and therefore more excited about the process moving forward. I saw more creative thinking as a result. That brings me up to date--this week we have two class periods, both of which will be dedicated to prototyping and testing designs. I'm looking forward to seeing what our students can do! Look for upcoming blog posts on our progress! |

Upcoming PresentationsPast

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed